Throwback Thursday: Rebuilding Old Ironsides

Imagine a ship is docked at your local port, and it towers over nearly every building in the neighborhood. That was the awesome sight of the USS Constitution in the 1790s, as it was under construction off Boston’s North End. Even without its masts, the frigate was the height of a four-story building. Only the steeple of the Old North Church could compete with that on the local skyline then.

We bring this up not only because the Tall Ships just visited Boston, but also because if you think about it, shipbuilding is a sister industry to our own land-based form of construction. Like a city high-rise, a ship is a unique, standalone structure (with its own name) that can take years to design and build. This feat was all the more impressive in the age of sail, when the endeavor relied largely on human brain and brawn.

And yet, in the case of Constitution—the last ship standing of the U.S. Navy’s original six, and the world’s oldest commissioned warship afloat—what might be more impressive is the dedication to re-building. Since she first put to sea in 1797 to protect Yankee merchant voyages, every American generation has produced engineers, architects, carpenters, and other builders who pitched in to patch up a national treasure. That holds true today, as the current crop of restorers apply high-tech tools to the preservation of “Old Ironsides.”

To see for ourselves, we descended into the dry dock.

The eagle of the sea

Undefeated in the War of 1812, Constitution was already a legend when she entered the brand-new, Quincy-granite dry dock in Charlestown, Massachusetts, on June 24, 1833. (That’s 184 years from this Saturday.)

That’s where and when the story of Constitution’s repeated extensive overhauls begins in earnest. At minimum, the frigate needed new planking, masts, rigging, decking, stem, head, and quarter galleries. After an erroneous report got out that the Navy planned to scuttle her, a young Oliver Wendell Holmes published an ode to “the eagle of the sea,” which rallied Americans to her defense and assured her survival. The Navy decided Old Ironsides would be the first ship to get a new treatment.

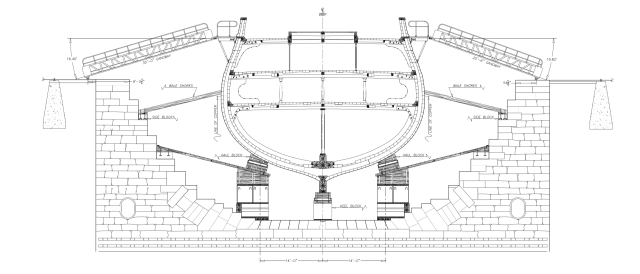

USS Constitution Section in Dry Dock No 1 (Rendering courtesy of the Naval History & Heritage Command Detachment Boston)

After six years of construction, the Charlestown Navy Yard’s Dry Dock One opened a week after its twin in Norfolk, Virginia. Both designed by Bay Stater Loammi Baldwin, Jr., they were the first large-scale dry docks in the States. Now the Navy could repair its fleet without resorting to the arduous process of “careening” a ship—that meant using weights to tip it over, first on one side then the other.

Dry Dock One’s 1940s expansion. (Photo courtesy of Charlestown Navy Yard Boston National Historical Park)

The dry dock was considered a marvel of engineering even decades later, and it was still used to service vessels during WWII. Although the dock had to be lengthened twice—from 341 feet to, eventually, 415—its width has remained the same, 86 feet at its widest point. “The interior of this dry dock was so well designed in the late 1820s,” said Margherita Desy, the official historian of the Navy’s Boston detachment, “that with the right shoring, you can put a flat-sided vessel in here, you can put a submarine in here—you can put vessels in this dock that could not have been conceived of by Loammi Baldwin 184 years ago.”

The coolest thing about the dry dock is how it works. Start by thinking of it as an artificial inlet. After a ship is towed in, another vessel called a caisson is towed to the entrance. (It’s not unlike other kinds of caissons you may have read about, here and here.) The caisson is filled with water and sunk into place.

Your fearless blogger drops in to the dry dock. (Photo by Patrick Kennedy)

Then the dock is drained—slowly, so as to ease the ship onto its keel blocks. While the ballast water at the bottom of the caisson weighs it down, the pressure of the harbor beyond holds it at the dock’s seaward end, creating a watertight door.

When repairs are finished, the dock is flooded again, the caisson is emptied and floated out of the way, and the ship is towed back out into the harbor.

The operation requires a complex system of reservoir, tunnels, culverts, valves, and gates. In the 1830s, a steam engine powered eight pumps that could empty the basin in four to five hours. The caisson itself took 24 men working hand pumps 90 minutes to drain.

That old wood caisson is long gone, and even its 1901 steel replacement was replaced in 2015. And today’s pumps are diesel-powered. But though the dock’s technology has changed over 184 years, its basic principles remain the same. “It’s like with any tools,” Desy said. “We still use planes and saws; it’s just that we plug them in.”

Check out the time-lapse video of Constitution entering the dry dock in 2015:

Plugging in

Just as the pumps have been updated, the means and methods of restoring the ship itself have kept pace with the times. For Constitution’s current round of renovation, a naval architect used computer-assisted drawing (CAD) software to redraw plans for the work, make precise measurements, and document the project.

This CAD drawing shows the spar and rigging plan for Constitution as she will be rigged at the end of the 2015-2017 restoration. (Photo courtesy of the Naval History & Heritage Command Detachment Boston)

The 3D virtual model is a far cry from the quill pen that Joshua Humphreys used to design the Navy’s first six frigates in the 1790s. (A frigate, by the way, is a war vessel with at least three masts and one covered gun deck. It’s also a fun thing to say aloud, especially when you’ve given up on something.)

And whereas 18th-century loggers seemed to have their pick of trees from an infinite supply—the thick wild woods that covered most of the East Coast—modern timber concerns know to practice sustainable forestry. Indeed, there’s a grove in Indiana devoted solely to timber for the Constitution. To procure the white oak timber for the ship’s hull planking, the Navy set aside 150 white oak trees in the forest around a naval facility in Crane, Indiana. “Constitution Grove” was dedicated in 1976.

White oak delivery in Charlestown. (Photo courtesy of the Naval History & Heritage Command Detachment Boston/Margherita M. Desy)

“It’s a managed forest,” said Desy. “As the trees grow, their lower branches are trimmed and each tree is allowed a lot of sunlight. Because, to qualify as trees for Constitution, they have to be at least 45 feet in length from base to crown, and at least 40 inches in diameter at the base.” In 2015, thirty-five of the trees were felled, and eventually 350,000 pounds of white oak were delivered to Charlestown.

Here we should point out that “Old Ironsides” is just a nickname, earned when cannon balls bounced off her hardwood hull. It was sturdy New England white oak and dense, rot-resistant live oak from Georgia—not iron—that repelled the attacks. However, below the water line, the frigate’s hull has always been sheathed in copper, to keep out wood-eating shipworm. In fact, master metalworker Paul Revere imported an innovation from England (by way of a little industrial espionage) when he opened our nation’s first copper rolling mill to provide the Constitution’s second copper coating, in 1803.

Another innovative tool used in today’s restoration work is the Gemini Universal Carving Duplicator in the Charlestown Navy Yard’s restoration workshop. The decorative carvings along the ship’s bow—like much of the ship—have been replaced time and again. The most recent set (based on earlier drawings and models) dated to 1930. To produce a new set, carpenter Josh Ratty used the Gemini duplicator to trace the 1930 carvings with a blunt stylus hooked up to a router that mimics its motion, making the real cuts in fresh planks.

“It’s like a manual 3D printer,” said USS Constitution Museum spokesman David Wedemeyer. Check out Ratty and the duplicator in action:

The Constitution wraps up its current phase of restoration next month. Still seaworthy, still officially in service, she’s the oldest vessel in the world still capable of sailing under her own power. But rather than sail off into the Atlantic after leaving dry dock, she’ll stay at the Charlestown Navy Yard, where generations of Americans can continue to enjoy visiting her and hearing her stories.

Special thanks to the U.S.S. Constitution Museum and the Naval History & Heritage Command Detachment Boston. There’s plenty more info about the restoration work on the detachment’s blog. And consider a visit to the Charlestown Navy Yard this summer. (Note to our readers in California: you get your own dose of tall ships in September! See http://www.ocean-institute.org/tall-ships-festival.)

P.S. Safety being a prime focus here at Suffolk, we especially appreciated the following PSAs posted at the Charlestown Navy Yard…

This post was written by Suffolk Construction’s Content Writer Patrick L. Kennedy. If you have questions, Patrick can be reached at PKennedy@suffolk.com. You can connect with him on LinkedIn here or follow him on Twitter at @PK_Build_Smart.